Uh oh, the Earth *continues* to spin faster

Thanks to all the subscribers to the newsletter that fund our self-hosted infra and help make all this posting possible! I'm getting back into more fun bi-weekly Thursday subscriber posts like this one. I'm also taking suggestions for what other posts readers would like to see.

In late 2021, I had written about how the Earth was spinning faster, possibly due to global warming effects, and putting us at risk for a negative leap second. At the time, I was a bit skeptical that the trend would continue enough to warrant an unprecedented negative leap second. It's been a few years and I decided to check in on the IERS data plots to see where things were standing. And uh...

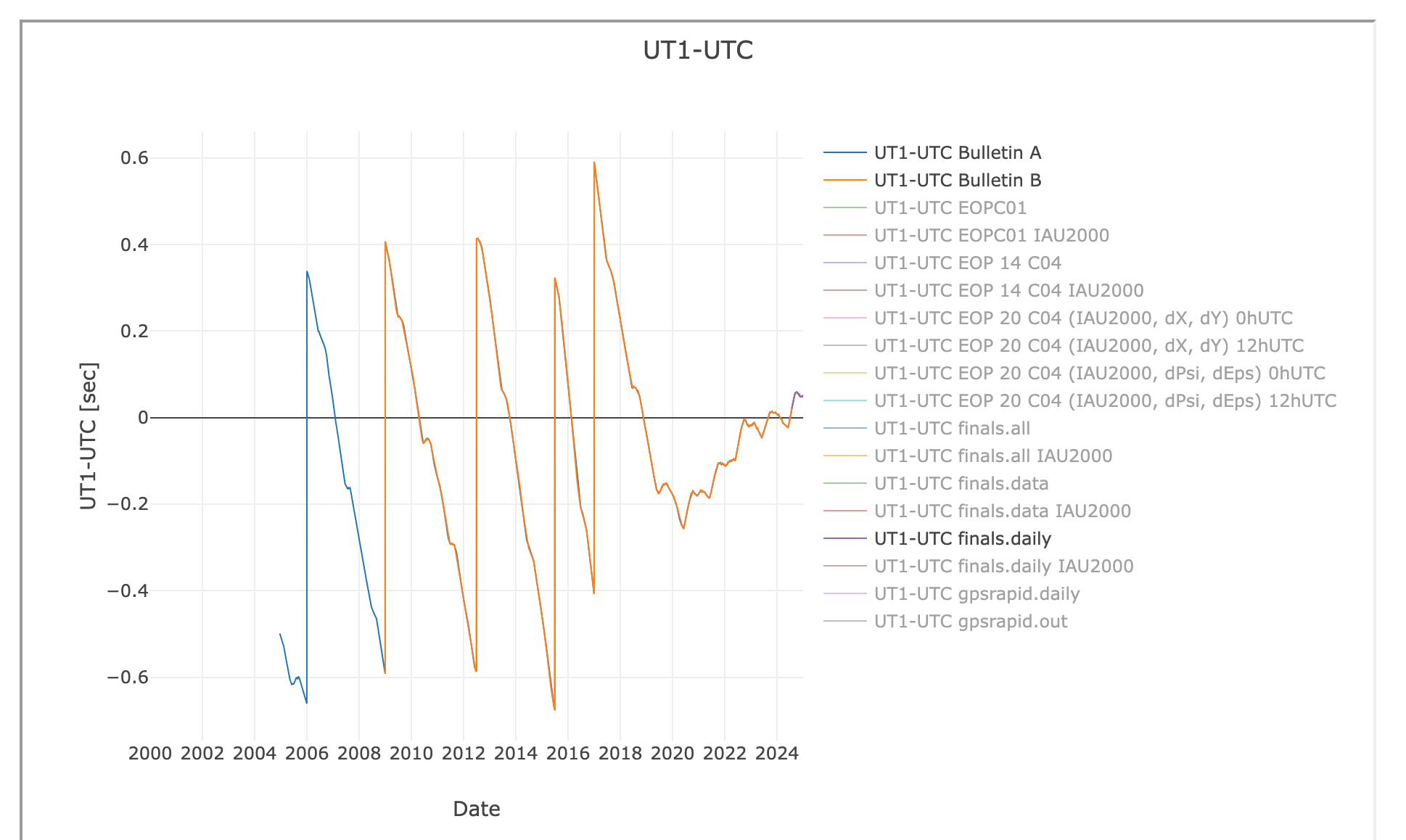

It's still happening! The Earth is continuing to speed up in its rotation. UT1 - UTC has, between the lowest point in 2022 to most recently in 2024, gained over 0.3 seconds.

Thankfully, the pace of speeding up has slowed down for now, but since there's a lot of seasonal and cyclical components to the Earth's rotation speed, I have no idea if it will speed up again or not. My data scientist magical trend squints tell me we still have a ways of accelerating to go.

If you have no idea what UT1-UTC means, there's a detailed refresher in the post I linked at the beginning, but the super condensed version is this:

UT1 is based off solar time and has by definition 86400 seconds/day. It determines the start of a day based off when certain specific fixed stars pass overhead. UTC is based off atomic clock seconds and also by definition has 86400 atomic/SI seconds in a day. Thus, the UT1 second is of variable length compared to the fixed UTC second, and you can calculate the gap between UT1-UTC.

Since the Earth has always (until recently) tended to slow down over time, when the gap between UT1 and UTC becomes too great, essentially over a second, a leap second is introduced into UTC that resets the difference so that the two time scales always have noon within a second of each other. This leads to those big discontinuous jumps in the chart.

Anyways, as you can see on the chart, things started getting weird around 2018-2019 and has continued to be weird ever since. When I first wrote about this, I only speculated this was a climate change thing, and hadn't really found many journal articles about it. Now that three years has passed, there's lots more papers about it.

A Nature abstract (which I don't have access to =P) has at least some researchers claiming that the melting ice caps overall changes might actually be enough to require a dreadful negative leap second by as early as 2029. That sounds pretty aggressive but let's roll with it for now.

Recall that 2029 is before the year that the CGPM had voted in 2022 to abolish the leap second "on or before 2035" for at least 100 years. The abolishment takes the form of allowing the difference between UT1-UTC to be greater than the current limit that triggers a leap second. So technically we were on the path to punting the issue down the road for a century already.

With these newer developments, the CGPM and related international bodies might have to rush the abolishment a bit earlier if the climate models hold true and they want to spare the world the chaos of every bit of time software on the planet not having ever tested the effects of a negative leap second. Since that involves international committees meeting and agreeing within just a handful of years, there's a surprisingly little amount of time for them to come to such a decision.

There are now plenty of research publications who are all pointing various fingers at various aspects of climate change for the increase in Earth's rotation speed. The key term to search for here is increases in the "length of day" published since about 2020. I haven't had the time and energy to sift through them all to see if they're reaching a consensus for what processes are contributing what effect.

The changes in climate are shifting mass around the planet through changes in the movement of water and ice. That also apparently shifts the shape of the solid rock under the ice caps. These shifts also then might have an effect on stuff deep within the Earth in the mantle and core. All of that collectively adds up to the Earth spinning faster.

Anyways, every so often I check in on this. It's a very slow process so maybe in a couple of years we'll get closer to the answer of whether we'll actually need to deal with a negative leap second or not.