Measuring UX friction in practice

A short while ago, I was musing on how one of the most common things we are tasked to fight against is this notion of "user friction".

The usual business idea is that if we can make a product so damn easy and smooth to use, then users will inevitably give us more money because we've removed every barrier we could that's stopping a user from adopting our product and giving us money. Of course, such a simplified worldview falls apart under more thoughtful consideration because, as the linked post above mentions, friction is often shifted around, not completely eliminated.

But today, I wanted to get more into the weeds about how friction is measured, and more importantly, what measuring even does.

In normal industry situations, the construct of "user friction" is pretty nebulous. Most times it's a handwavy shorthand for "a barrier that users experience that causes them to stop completing some task". But putting aside the exact definition for now, what does one do when one is asked to "find points of friction".

The qualitative side

In qualitative research contexts, researchers usually collect data about the friction points directly. For example, they can observe a user struggle to find the necessary button to proceed, or not have their credit card handy. While there's always room to debate on exactly what caused a user to experience friction at a certain point, people can usually agree that "some kind of friction happened". The user struggled to do what they needed to do, and that's not good from our point of view.

Researchers can also ask users why they stopped in the middle of a task to get an understanding of issues that can't be directly observed. For example, it's common to hear that a user hesitates to give an unfamiliar website certain kinds of sensitive information like name, address, credit card info because they inherently don't trust the website. Hearing stories like that provides a lot of details that teams can use to help users overcome whatever barriers they're encountering.

To the extent that you believe in the soundness of self reported measures from interviews and observational techniques, you can find many examples of places where things don't go perfectly smoothly for a user.

For many product teams, especially ones that don't have the ability to study thousands of users at scale, "looking for friction" boils down to applying these sorts of methods and working closely with your actual users to find places that aren't working as well as can be. Sample sizes rarely play a huge factor in analyzing the data that comes from these qualitative studies because very often, teams decide that "even one person who can't use our product because we buried the most important button is one too many". Big issues sort themselves out pretty easily, while small issues just don't seem as urgent.

When used in this way, there's not a huge need for a precise technical definition of what "friction" is because it's honestly just a framework for continuous improvement. You keep running studies to find friction until you find increasingly smaller and smaller issues.

For the many places that don't have quantitative UX researchers on staff (which is likely the majority), this way works well enough.

Quantitative friction measurement is often supportive

Meanwhile, quant researchers have a much trickier time working with friction because it's very hard to measure directly. Friction is often what happens in-between steps of a process, not on a step itself.

Most quantitative measurement techniques involve recording a data point when something happens – users click a button, loads a page, a server responds, etc.. Most metrics/telemetry systems are not designed to give status reports every second about everything happening because it skyrockets the cost of data storage, processing and analysis for very little information gain. But because we trigger logging events when something happens, friction is the thing that prevents an event from being logged. It happens outside our measurement framework – we can only see the ghosts and shadows of the effects of friction. This makes us very much aware of how many things we aren't tracking in our telemetry.

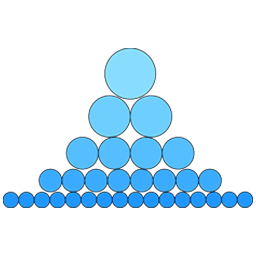

In that light, the most common tool we have in the quantitative UX researcher toolbox is a simple diagram that calculates the number of users that drop off at various steps within a linear flow. (We're going to ignore the messy case where flows branch and interweave and become nightmares to reason about or even just visualize.)

As an example, if our e-commerce checkout flow takes 5 steps, and of the total user count we lose 30% -> 10% -> 50% -> 5% of users as they transition from step 1 to 5 leaving us with only 5% that successfully get through, then our eyes naturally lock onto that 50% loss and go "aha! the most users are disappearing here! There must be friction there!". We could also of course look at the initial 30% and argue there must be friction there, or honestly any of the other points because any dropoff might be a sign of some kind of friction. There's arguments that can be employed to draw focus on essentially any step you want. If you want to be charitable, you could say the method is very adaptable. If you want to be blunt, you can say the whole methodology is completely inconclusive and based off vibes hiding behind numbers.

Quantifying user loss didn't really identify where the friction is aside from "somewhere between steps 3 and 4 or steps 1 and 2", and those numbers certainly cannot say what the friction is. All the numbers did was point out that "if we somehow fix the friction here we're going to likely have an effect on the biggest chunk of disappearing users". It reduces product improvement to a cynical numbers game where maybe our interventions can make things better, or maybe not.

Regardless of what you believe, the critical piece of information about what the friction point for users actually is never comes out of a quantitative analysis, it has to come from qualitative work. At the very least, someone has to go to step 3 and figure out what is causing the trouble with step 4. This is work that a quant researcher will often do because we're just as unsatisfied with the initial answer as anyone else, but it's a step that cannot be skipped if you want to make a coherent statement. Sometimes self testing and observation doesn't work and it requires interviewing actual users to get at the answer. Regardless of who does the work, there's no guarantee that whatever friction is found can even be fixed.

So, quantitative methods for "finding" friction actually serves as a prioritization and highlighting mechanism. It's extremely rare that quantitative methods alone will uncover some new friction point that no one knew about, but this is what a lot of managers and executives seem to expect when they request that qUXRs take a look at friction points. Execs always hope that we will find the next "one magic fix" that will double revenue numbers, and it's nigh impossible to deliver. Every friction point I've ever uncovered had already been found by a qualitative researcher before. They just weren't able to convince a team to work on a fix yet.

Instead of finding new friction points, the best case scenario for quantitative work on friction is to highlight how an area of friction is so important it must be fixed. I've definitely worked on projects where teams wanted to work on other projects but the data managed to convince them that one particular thorny issue they didn't want to deal with had outsized impact on the lives of many users and needed addressing.

Now, inferring friction from gaps in log points isn't the only way to operationalize the notion of friction. For example, if you had access to eye tracking data, you possibly tailor a more direct measurement of friction with that data. Alternatively, if you had very specific hypotheses for what friction does exist you may be able to create a very targeted measurement. For example like if you think users can't find a button, you can trigger a logging event the moment when the button is rendered in the browser window (meaning if most users never see that impression event, not finding the button is very likely the issue). But again, those methods require iteration, hypothesizing, and working with qualitative methodologies (and researchers) to come to a complete picture of the situation.

But you're still shuffling things around

But even with spending all this time, energy, and expertise into identifying friction, the vast majority of projects end with "and there's not much we can do." No amount of measuring, testing and design will ever make it so that users don't feel at least somewhat hesitant about spending money. No amount of making a process "easier" will ever answer the question of "should the user even be doing this in the first place?"

This is why it's important for us as researchers to keep an eye on the bigger picture. Friction work is often tactical work with very finite payoffs — the main upside you're going to see is losing fewer users along the way then before. There's inherently a ceiling that even perfect improvement can bring. The only way to expand a product's market is to increase the scope of the work to questioning what the product is and what it should be.

Standing offer: If you created something and would like me to review or share it w/ the data community — just email me by replying to the newsletter emails.

Guest posts: If you’re interested in writing something, a data-related post to either show off work, share an experience, or want help coming up with a topic, please contact me. You don’t need any special credentials or credibility to do so.

"Data People Writing Stuff" webring: Welcomes anyone with a personal site/blog/newsletter/book/etc that is relevant to the data community.

About this newsletter

I’m Randy Au, Quantitative UX researcher, former data analyst, and general-purpose data and tech nerd. Counting Stuff is a weekly newsletter about the less-than-sexy aspects of data science, UX research and tech. With some excursions into other fun topics.

All photos/drawings used are taken/created by Randy unless otherwise credited.

- randyau.com — homepage, contact info, etc.

Supporting the newsletter

All Tuesday posts to Counting Stuff are always free. The newsletter is self hosted. Support from subscribers is what makes everything possible. If you love the content, consider doing any of the following ways to support the newsletter:

- Consider a paid subscription – the self-hosted server/email infra is 100% funded via subscriptions, get access to the subscriber's area in the top nav of the site too

- Send a one time tip (feel free to change the amount)

- Share posts you like with other people!

- Join the Approaching Significance Discord — where data folk hang out and can talk a bit about data, and a bit about everything else. Randy moderates the discord. We keep a chill vibe.

- Get merch! If shirts and stickers are more your style — There’s a survivorship bias shirt!