When the AI comes for my coding job...

I got interviewed by Stephen Paff about Quant UX research in two separate audio parts that recently got published. It was one giant interview weaving between data science, social science, communication and doing research in industry. Check it out if you’ve got the time!

A couple of weeks ago, I was making snarky comments about how there are techbros out there who are claiming to empower their customers in UX Research without… pesky research participants. In classic “question the assumptions” tech thinking, they imagined a world where the expensive process of asking real humans for their thoughts and opinions would be replaced with a LLM pretending to be human. Surely this technology, despite having no corporeal body or human experience to begin with, could speak as-if it were human in a specific stereotypical role and give useful, novel, feedback. There was… a lot of eye-rolling at the idea — but that’s never stopped people from selling snake oil to naïve consumers before!

This week, we can take a look at AI trying to take my job in a much more reasonable way. It’s something that if you squint at the problem enough it miiiiiight be within reasonable scope — coding free form text.

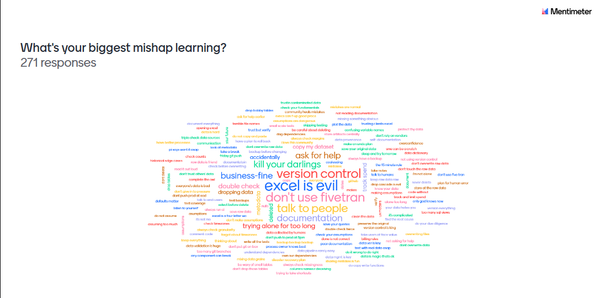

If you work in “quantitative UX research” for long enough, you’ll inevitably be asked to tackle a variant of this problem — “we have a bunch of text from [some source], it’s all users saying stuff we’re interested in, can you find a way to extract out the themes and patterns for us to use in our work?” This data is often from things like user surveys, or support ticket cases, or social media comments from the internet. People are convinced there must be gold lurking within all this text, if only there were an alchemist who could extract it.

For the sake of argument, let’s just accept at face value that there does exist some kind of useful knowledge buried within all that text. It’s likely not as earth-shattering as the people requesting the analysis believe, but there’s probably something worth learning from the data.

The generally accepted way to “do this right” is to have trained humans read the text and manually classify them into categories/themes. In the social sciences, we call this “coding”. It has nothing at all to do with programming or even computers. As you can imagine, it’s a very expensive, manual and iterative process. Yes, we very often do this work in a spreadsheet.

People have to read the text, propose categories, then label the texts according to the categories. Very often you have to go back and modify categories as you discover that they’re not quite distributed in the way you want (too sparse or too clustered together). Then, unless you like suffering alone, there are procedures to train multiple human coders and then check how often they agree on labels via inter-rater reliability measures. For long-running or otherwise important social science projects, whole coding guidebooks are written up full of procedures and training examples in order to make it so that individual coders will largely code things the same way as everyone else. Obviously, doing this at any sort of scale is extremely expensive because humans can only concentrate and read so many chunks of text before their brains melt into incoherent puddles.

Even years before the present, most people in this field have tried various NLP-based methods to group and cluster text together using a computer. We’d use things like heuristic rules, bag-of-words tricks, and word embeddings like word2vec for this task. We all know that human language is very likely out of scope for pure machine interpretation, but at the least maybe we can simplify the task by at least sorting “related-ish” text together, and maybe at least filter out the inevitable meaningless garbage that makes its way into such data. Even such simple improvements would make coding hundreds and thousands of text comments much quicker.

So, put in abstract terms, the task for the human coders is to derive categories from a bunch of text input. The humans will often leverage all the knowledge they have, including “we plan on answering this research question so we need to distinguish this specific thing clearly” to come up with categories they think will occur multiple times in the data set. They’ll make guesses and very often have to backtrack and make adjustments as things evolve and they become more familiar with the data.

In a word embedding vector way of stating things, we’re essentially dumping this document vector into the high-dimensional word space, and clustering them in some way. LLMs, having giant high-dimensional word space embeddings within them, might work for this task!

And that’s what some people did. In a small study, some people compared three human coders against three ChatGPT based coders to see how the LLM performed while doing the same task. The specific prompt they used was this:

As a UX researcher, you are tasked with analyzing the dataset provided below, which contains answers to the question, “What are some problems or frustrations you’ve had with the XXXX website?”. Your goal is to classify each numbered statement according to common themes. Create as many categories as necessary to group similar statements together. If a statement fits multiple categories, include it in all relevant categories.

START DATASET:

[dataset numbered by participant]

END DATASET

After analyzing the dataset, follow these steps:

List the categories you have created, along with a brief description for each category.

For each category, list the numbers of the statements that belong to it.

If there are any statements that do not fit into any of the categories you have created, list their numbers separately.

The overall conclusion was that, ChatGPT did surprisingly well.

The themes generated were roughly similar to what humans created, after people took some time to check to see what the categories actually meant. More importantly, inter-rater reliability measures were quite good (roughly in the area of “moderate”/”substantial” agreement for Kappa), within the range of where you’d want it to be with a bunch of humans.

In general the IRR in human-human and gpt-gpt coder pairs were the highest, but human-gpt pairs were slightly less so. For whatever reason, the humans disagreed with the computers slightly more.

So, what, coding is done for now?

As an overall LLM skeptic, I’m generally surprised how well a LLM seems to behave for this specific task. I suppose it’s somehow leveraging the internal word vectors its learned.

But despite this, I’m still going to be very cautious about deploying any such technology. The authors cited having trouble crafting a good prompt that got the LLM to do what they wanted. Depending on the prompt, it wouldn’t generalize text into themes and instead just listed the data out. Prompt engineering is a black-box endeavor, so you hope it all works out.

But more concerning to me was the third caveat the authors cited:

- Caveat 3—Need to run ChatGPT multiple times: One way to deal with the limitations of ChatGPT for this task is to run it multiple times. In this study, we ran the same prompt against the same data three times. We expected to get kappas over .900 for comparisons of these runs, but instead, they ranged from .584 to .784, close to the range we got for three human coders (.683 to .726). Clearly, ChatGPT is not deterministic.

The non-deterministic behavior of ChatGPT made it so that multiple runs of the same prompt/data would yield very different inter-rater reliability scores. So each run is like you’d spin up a new imaginary coder, who might do things completely different from anyone else. While the IRRs between runs are still decent (.584 is still respectable), as someone who doesn’t like non-deterministic analyses, it makes me itch inside.

Yes, yes, you can argue that the humans who are working on coding tasks can be pretty non-deterministic too. While the overall themes are probably going to be similar, there’s a lot of one-off decisions and fatigue effects make it impossible for a single person to replicate their own coding scheme if asked to do it a second time.

At the very minimum I will want a human baby-sitter of some sort that can do spot checks on the output to make sure things appear to behave as we’re expecting. There’s also going to be a lot of work done to interpret categories that are generated and make sense of them. It's likely that not all the categories returned are useful, or potentially at the right level of detail.

But in terms of clustering text together to make it easier for humans to apply sense-making to a data set, it looks like a promising area to explore the limitations of. And I’m sure the more people try to apply this methodology, the more we’ll find the hidden flaws inside.

But hey, even with all these caveats, it still means we are one step closer to achieving what we had been wanting to do for years, cluster text together according to “themes” at massive Big Data (tm) scale at a “good enough for a first cleanup pass” level. Remember that our initial goal had set a pretty low bar of simplifying the dataset so that it would be easier to do intelligent manual analysis on the remaining bits.

That alone would save thousands of hours reading raw text until our brains rot from the monotony. So I’ll gladly take it when someone refines this technique a bit more.

Standing offer: If you created something and would like me to review or share it w/ the data community — my mailbox and Twitter DMs are open.

Guest posts: If you’re interested in writing something a data-related post to either show off work, share an experience, or need help coming up with a topic, please contact me. You don’t need any special credentials or credibility to do so.

About this newsletter

I’m Randy Au, Quantitative UX researcher, former data analyst, and general-purpose data and tech nerd. Counting Stuff is a weekly newsletter about the less-than-sexy aspects of data science, UX research and tech. With some excursions into other fun topics.

All photos/drawings used are taken/created by Randy unless otherwise credited.

randyau.com — Curated archive of evergreen posts.

Approaching Significance Discord —where data folk hang out and can talk a bit about data, and a bit about everything else. Randy moderates the discord.

Support the newsletter:

This newsletter is free and will continue to stay that way every Tuesday, share it with your friends without guilt! But if you like the content and want to send some love, here’s some options:

- Share posts with other people

- Consider a paid Substack subscription or a small one-time Ko-fi donation

- Tweet me with comments and questions

- Get merch! If shirts and stickers are more your style — There’s a survivorship bias shirt!