Two Stories About Labeling Data by Hand — It Still Works

Sure it’s a pain in the butt and has its own issues, but human brains are still amazing

I know. Labeling data by hand can be super tedious and mind-numbing. It’s about as far from glamorous and sexy machine learning work as you can get. Aren’t we, as super smart data scientists, supposed to be above this drudgery that is often foisted onto interns, grad students, or Mechanical Turk?

Actually, no. In a lot of situations, I think it is less painful (and faster) than many alternatives that involved unsupervised learning methods. It also yields very important specific domain insights that I’d argue a good data scientist absolutely needs to be effective in their chosen industry.

Perhaps it’s because I cut my teeth in the industry as data analyst a decade ago, cobbling together insights the hard way. Or maybe it’s my social science background where manual coding of responses was a very important tool in our quantitative toolbox. Still, I’m not the only person who believes this.

In general, I find that hand classifying data is the most useful when you’re thrown into a situation where you need to: 1) both learn to understand the data set/problem space as the researcher and 2) come up with a classification system.

In such situations, it’s hard to make an automated system that works to an acceptable degree right out of the box. Sure there are unsupervised methods you can try to do various forms of clustering and then classifying, but when you’re unfamiliar with the problem space yourself, it’s not entirely obvious if the clusters you get are valid and usable. Since there’s literally no ground truth to stand on, you might as well dive in yourself to build some semblance of ground truth, both in your mind as well as for your classifier.

Can human classifiers be wrong? Definitely. Have unconscious (or conscious) bias? You bet. Miss out on important features? Of course. But for the applications I usually operate in, those don’t matter. We need something good enough to start, to build a test case. Once things are bootstrapped, we can see how things perform and check for issues.

Here’s two illustrative stories from early in the 2010s, when tech was different (but not all that different).

Technical note: I use the verbs to “code” and “label” interchangeably throughout. Just habit.

Story #1, Go Classify Some Businesses at a Hackathon

In 2012, I went to a data hackathon of some sort, I believe run by the folk at Data Kind in partnership with various government agencies and non-profits. We split up into groups, each group got some kind of problem that needed data help and we all tried our best to be useful in a couple of hours. The output could be a model, or a methodology, or just about anything useful.

For my group, we were partnered with an agency for NYC, I forget which one. Our task essentially boiled down to we big csv files of businesses and the specialized licenses they have (cigarette retailer, billiard room, debt collection, sidewalk cafe, general vendor, etc). The businesses also had their registered address with the building type, whether there was a restaurant license or liquor license associated with the site, and some other details. The goal was to see how businesses and licenses go together, so that if a business happens to be missing a license (say, an unlicensed bar) it can be flagged.

My team of four or five people (I think?, I’ve forgotten some details but have copies of the old data files to review) had plenty of super smart people, a few big names of the data science world. To start, they pulled out R (a language I still don’t know) and started working on figuring out how to ingest the various CSV files we had so they could run various analysis (similarity calculations, etc).

Diving in

Seeing that they had the coding side in the works, I went ahead and tried to make myself useful on the side by doing what I normally do, slogging through the raw data to get a sense of things. Because we ultimately wanted was a way to independently classify a business entity based on what licenses it had, WITHOUT using the existing business classification codes, I had a hunch we were going to have to find a way to classify these business entities with very very little data outside the label we’re not supposed to use (because we’re trying to predict it to find discrepancies).

The alternative was to do a 2 step classification system where we would 1) group licenses together, and hopefully properties of the business would naturally cluster, then 2) take the clusters and use them to form a classifier that can catch businesses that don’t have the correct licenses. Both of those had no guarantee that business/license clusters would actually form in any sensible way. With only ~10k entires of licenses (with a given business potentially having multiple licenses and rows), there may be too much noise.

As I scanned through the businesses and tried to guess what the businesses were, oddly enough, I found it to be surprisingly easy. I’d look at the name of the entity, and would constantly see things like “Fred’s Laundromat” or “Sunshine Cafe, Inc”. I realized that while there wasn’t any strict requirement, people often named their business entities after the business they were engaged in. Practically no one would open an auto shop named “Mary’s Coffee, LLC” This was an insight that we never would have found if no one sat down and read through piles of data.

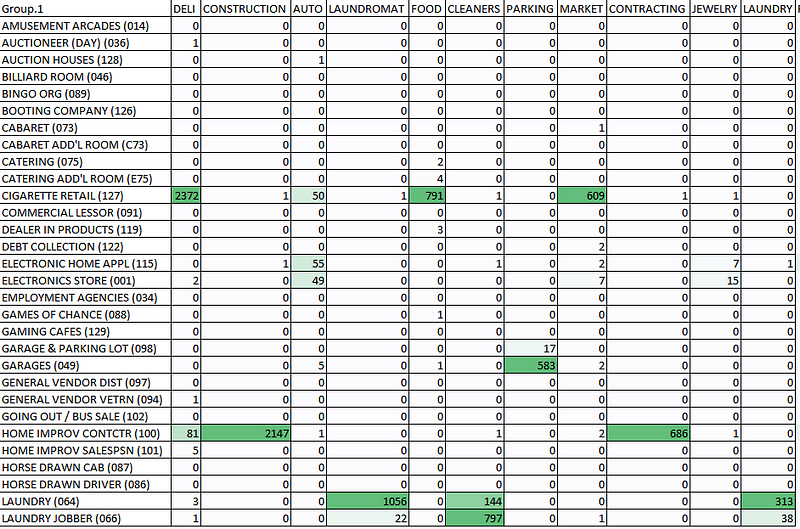

What I wound up doing was compiling a list of key words that I felt was highly indicative of being a certain kind of business, for example: “Auto”, “Deli”, “Duane” (for the Duane Reade pharmacy chain), “Supermarket”, etc.. We then analyzed what licenses were associated with those words. For example, the cigarette retail license often was associated with businesses with “Deli” in the name, but also “Food” and “Market”, and occasionally “Auto”. The table below shows some of the associations we found.

The number of business entities w/ a word in its name (top row) vs business licenses associated (down the left)

By the time we got to this point we were a bit short on time, but what we essentially built was a system that can take in a business name and generate a list of the probable licenses it would have. It’s not going to classify everything, but it was a much stronger way of aggregating businesses together than the other available features like address, building type (2-family vs elevator co-op, etc), retail square footage.

With this initial classification, we could then experiment w/ the other features to see if there are any meaningful clusters, because we had semi-hand labeled thousands of businesses to start with. This was our (fairly) firm ground truth that would allow us to leverage into the rest of the data set.

Sadly, the data hackathon ended soon after, and I have no idea what happened to the model, whether it was used or not. But hopefully it helped someone get closer to the goal.

Story #2, Make Some Group Categories for Meetup

I can’t remember exactly when this project came up, but around the time Meetup did their first few runs at making group discovery possible outside of straight keyword search, so roughly 2012-ish? Their categories have changed quite a bit since when I helped build out the system, so I’m sure it has nothing to do with the existing system and it should be safe to talk about here.

For background, Meetup groups originally, pre-2011, had up to 15 “topics” associated with them. These affected what users would get notified when you group was announced, and you could use it sorta browse for groups. The crazy part is that the topics were completely free-form user strings, created by the group organizers. There was some light curation to keep people from putting in naughty words, but otherwise you were free to write single words like “photography” or whole sentences like “taking photos of cheeseburgers at night”.

The problem was that while there generally was a leading topic for most kinds of groups, like most photography groups used “photography”, not all of them did. This is most prominent with “Stay at home moms” groups vs “Stay at home dads”, both are essentially parenting groups, but a group might choose just one.

Well, if we’re to have a better way to find groups, there needs to be a way to organize groups by some kind of category. We needed to distill 1–15 topic tags into 1 (maybe 2) categories. What should those categories be? While newly made groups get reviewed by humans anyway and can be categorized manually there, how do we handle the ~100k existing groups?

Coming to this problem blind, you might be tempted to analyze and k-means cluster all the topics strings based on what groups used them. It probably would have worked since we knew we would like K to be a “manageable number” (under 30-ish). It would have taken some tuning and trial and error, but sounds doable.

The plan

Instead of taking the k-means approach, I went in a different direction. Working on a hunch (out of working deeply with Meetup’s internal data for 2–3 years), I had a feeling that “the most used topics probably were informative enough”, meaning I could ignore the super long tail of topics.

So instead, dumped out all the topics that had more than a certain number of groups associated with them (> 50 groups or something similar, I forget). This yielded a list of ~1800 topics, compared to a giant list of > 15k topic strings.

After that, I spoke to my qualitative research partner in crime, we split the data set, and just sat down to categorize the topics by hand. Just like like coding free-form survey responses, we created categories as we saw fit, and plowed through.

After creating that mapping, I created a dead simple algorithm to assign a group a category, 1 classified topic = 1 vote for a category, the category with most votes is the group’s category. With just this dumb algorithm, we covered roughly 85–90% of all existing groups. Spot checking a random sample of groups showed that the categories in general were pretty accurate (I forget the details, but mid-high 90% agreement w/ humans).

How did we handle the ~10–15k groups that couldn’t be categorized this way? We made a simple web tool for it, and asked everyone on the customer support team to chip away at it during quiet periods in their shifts. It didn’t take all that long, maybe 1–2 weeks of time to classify everything.

Moving forward we used the same algorithm to suggest what the category should be, but the support team would check and change it when they review new groups for TOS/quality anyway.

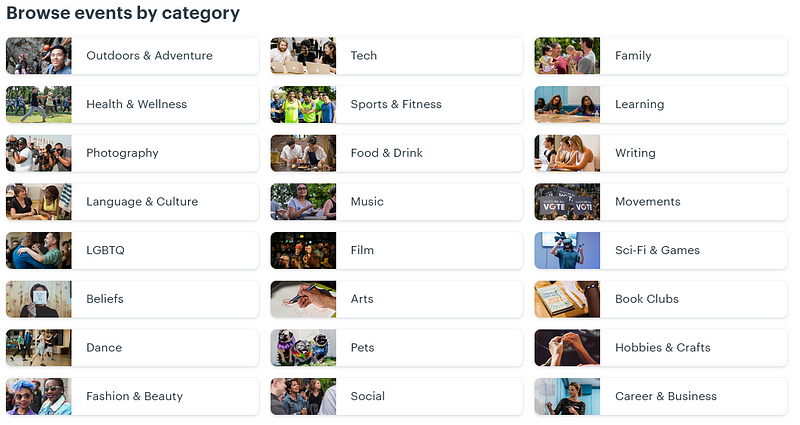

I’m sure whatever system they use now is different from the one that I helped build so long ago. The current categories seems to fix some issues we found in v1. For instance, One of our initial regrets was certain categories were “too big”, too many business/startup/entrepreneur/investing groups all lumped together under “Business”. We should have gone back and balanced things, but we chose not to because we weren’t sure how categories were going to be used at the time.

Meetup’s current categories (2019), about half of which weren’t ones I put together almost a decade ago

So Roll Up Your Sleeves

Want to give it a shot? Here’s some quick tips.

Set up a good coding environment. The act of labeling should let you get into a flow where you can crank out accurate labels rapidly. When you minimize that friction of having to click links or have your eyes jump around the screen, you help minimize the mental fatigue that introduces unforced errors. Then, make sure to take frequent breaks (I love snack breaks) when you feel fatigue setting in.

If you have multiple coders, make sure everyone agrees to code in similar ways (more formally you’d have a coding book), communicate frequently, check your work. For more rigorous stuff, make sure you do sanity cross- checks and check the inter-rater reliability.

Finally, find ways to spread out the work. Coding is MUCH more fun in a group setting. We can trade jokes about strange examples, or discuss weird edge cases on the fly. Plus having another person physically there doing the work with you helps with focusing.

But, this won’t scale!

Sure, if you’ve got 50 million things to code, you’re not going to manually do them all. But going from 500 to 5000, or even to 15,000 labeled entries will make any classifier you make perform so much better. You should then be able to scale up with much more confidence than before.

Hopefully, my little stories have convinced you that the totally unsexy, oftentimes mind numbing and painful work of hand labeling data is a super useful tool to have in your toolbox.