Skill Windows into the Data World

Oops!! I just realized when I published this I forgot to check the box to send it out as email! =O I blame being sick with COVID on taking 2 days to realize this (family and I are recovering fine.)

Over the weekend, Vicki wrote a blog post, “Git, SQL, CLI” (it’s nice and short, just go read it). Within, she proposed that there are 3 basic “tools” that are essential for working with data, despite working across multiple companies and environments. (For some definition of “tool” and “essential”. We’re not getting into that.) Essentially, those three tools are what someone who’s interested in learning data science today should learn because they provide highly portable skills while also providing a foundation for learning other skills and will likely be relevant for decades to come.

My initial 15 second reaction was “I don’t think I disagree with this…”, based entirely on the fact that I’ve worked at 6 companies in a wide mix of environments and they seem to make sense. But that raises the question — WHY don’t I disagree with it? Out of the gajillion buzzwords that I and everyone else puts on their resume, why is it that I feel that those 3 topics cover a significant part of the fundamental data science skill set? If I can figure out if there’s any magical properties about those three tools, maybe it’ll help uncover any gaps.

In my mind, the web of knowledge that’s needed in data science is pretty ridiculous and interconnected (as webs are). There’s all the statistics/methods stuff, AI/ML stuff (for some fields), programming/computer science stuff, and business/domain knowledge stuff. Even if we don’t typically have the full depth in any of the domains like an expert is, we still have to fluidly use skills from all of those in conjunction. A lot of the value we bring derives from being able to bring the nuance and techniques of all these fields to what we’re working on.

So there’s a lot of theoretical book knowledge that we have to learn in all those domains, but all the theoretical stuff eventually has to find a practical, applied, interface with the real world. In the end we’re an applied discipline and need to manifest real world outcomes.

For example, all the programming/computer knowledge has to manifest itself into functioning code and systems that do stuff in the real world. Stats needs to translate into running experiments and decisions. Domain knowledge needs to translate into identifying and answering the right questions, to the right depth.

But while some people might have no problem learning a bunch of theory up front before touching actual tools, for many others project based learning approaches where learning happens by working on projects is more effective. This is where Vicki’s list comes in.

Git, SQL, and CLI tools, what does learning these tools bring us, and how’s that fit into the big picture?

SQL

Learning SQL provides data access and lets us do the rest of our jobs by letting us have data. Since it’s available almost everywhere, I can’t think of an instance where learning it is a mistake.

SQL, as a language, is relatively simple to pick up. While people regularly complain about its quirky syntax and the many dialects that can’t port to each other, someone can learn the basic aspects of SELECT with a couple of days practice.

But when you start mastering SQL by using it often on increasingly larger systems and problems, it leads to a surprising amount of really powerful stuff. For example:

- Query optimization leads to learning about indexes, partitions, row cardinality, and in the case of distributed noSQL data stores, some aspects of optimizing workloads for distributed computing

- Creating data schema, including normalizing data and maybe possibly de-normalizing data for performance reasons in specific contexts

- Learning how engineers and computer systems put data into databases, and being able to see how the data is a reflection of the business logic. This lets you debug certain bugs and issues just from seeing the output data

So even though you start by learning this simplistic language for requesting data out of a database, it quickly starts bleeding into other topics. What’s also nice is that you’re often forced to learn these things organically. Optimization naturally happens when you work with increasingly larger data sets. You’ll learn about data schema by touching production systems with schema that are usually normalized for you (so you learn by example).

Git

Version control is essential to engineering workflows, and git’s the de facto standard used by most people these days. It’s pretty notorious for being confusing to use beyond the most basic commands of adding/committing/branching. I’ve certainly wrecked my local repo bad enough that it was easier to hard reset them than recover.

What’s interesting is that in certain data science workflows, such as exploratory analysis, version control isn’t used as often while they’re critical in things like production modeling and data pipelines. So depending on what your day-to-day work looks like, you might not actually use git all the time. I certainly don’t.

But in addition to merely learning about code versioning, learning git opens up access to the main engineering codebase and all the tooling that engineers use to launch stuff into production. If/when you ever start putting code into production, or just need to search for code to check for a telemetry flag or something, you’ll be relying on these skills. If you haven’t done development work before, git (along with sharing a programming language) is your gateway to working closely with engineering.

Through this gateway, you’ll probably touch the CI/CD systems, code review systems, writing tests where applicable, QA processes, and beyond. You can’t really play with any of those things until you submit code in the way everyone else submits code, and that is increasingly going to be git (or some equivalent).

CLI

“CLI” is a bit of a cheat since it’s an unbounded set of tools all accessible via the command line. While I take Vicki to (mostly) be meaning “all the stuff in the typical Linux install that’s Unix-like, plus some extra bits”, it sorta can cover a ridiculously wide array of tools once you start downloading utilities.

Either way, to many people the start text-only nature of the command line is very intimidating at the start. But being super comfortable on the command line, which these days implies being super comfortable with Unix-like systems and possibly Windows Powershell if you happen to be in that environment, yields lots of benefits.

Comfort at the command line is the gateway to scripting, scheduling, and automating tasks. Much of the messy “glue” work that happens in data science effectively grows out of just chaining basic CLI commands together, even with the advent of tools like Airflow that try to take up some of the work. Diving even deeper into the world of CLI starts delving into the world of system administration and managing services and servers if you’re interested.

The patterns within, and other candidates

So the three tools above some good properties:

- You’re air dropped into a giant unexplored web of knowledge

- The tool provides a relatively easy starting point and accessible end goal

- The initial use cases are well documented with lots of tutorials, blog posts

- Once you get started, you naturally get pulled into advanced topics as you increase your usage

So the question is, are there any other tools that fit this broad pattern?

I’m on the fence about wanting a general purpose programming language — Java, Python, BASIC, Javascript, it doesn’t really matter so long as it has loops and functions. You want those features I started on VBA and some C. CLI tools like bash technically have those features but the syntax is painful. General languages then come into their own domain of expertise when APIs, libraries, building services, and integration with other systems starts coming up down the line.

The problem with wanting to push for adding a general purpose programming language to the list is that they’re too general. Since they can do everything you can dream of, we constantly have students asking for project ideas to help them learn. We need to preface the ask with some kind of purpose like “connect to the API, or automate your SQL report”.

Surveys!!!!

What I really really want to find is a “tool” of some sort that throws people a few other webs of knowledge — data collection and statistics, because the current tool list is leaning towards folk who are coming into data science from a non-CS background (a traditional data analyst, maybe social science, etc). But the problem here is that “tools” in those fields aren’t really the same thing as a “tool” in a computer science context — they’re more “methods”. There are still “tangible tools” like SPSS, Stata, R, but right alongside them are abstract tools like surveys, experimental designs like A/B tests, etc.

But if I had a magic wand…

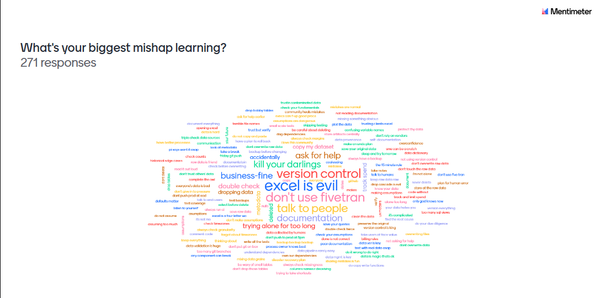

I’d love if everyone learning data science would run a short survey and then seriously analyze the results to try to come to a conclusion. Surveys are extremely simple to do, but the depth you can go into refining the methodology is nigh infinite. Even doing a poor one throws you hard against all sorts of issues that we must confront when working with data. Am I measuring what I want to measure? How do I know? Are people understanding my questions? Are they biased in their responses? Who’s responding? What can I say about the data I’ve collected? Why is all the data coming in messy? If you’re comparing subgroups in the data, how can you compare them statistically? Can you draw any inferences about the groups?

Interestingly, I feel that just touching surveys is more useful to learning than the posterchild of data science, A/B testing. While the mechanics of A/B tests are extremely easy and well documented, you’re also not forced to confront the fundamental pillars of the method very much. The math and tooling for an A/B will gladly spit out a result even if you completely mess up the randomization or data collection. Whereas for a survey, there’s a lot more manual analysis required that gives you opportunity to think. I also can’t think of very many industries where you’d never use survey methodology at all, so it’s also pretty safe for everyone to pick up.

Now, if only I could come up with some ideas for a process for identifying “tools” that help people bits of domain knowledge…

Totally unreleated to this week’s post, but I came across a video of Adam Savage going on a 45 minute, largely unscripted nerd-out on measuring things and metrology. It’s a bit rambly at parts, but I found it quite interesting, and you all know I’m a sucker for metrology.

About this newsletter

I’m Randy Au, currently a Quantitative UX researcher, former data analyst, and general-purpose data and tech nerd. The Counting Stuff newsletter is a weekly data/tech blog about the less-than-sexy aspects about data science, UX research and tech. With occasional excursions into other fun topics.

All photos/drawings used are taken/created by Randy unless otherwise noted.

Curated archive of evergreen posts can be found at randyau.com

Supporting this newsletter:

This newsletter is free, share it with your friends without guilt! But if you like the content and want to send some love, here’s some options:

- Tweet me - Comments and questions are always welcome, they often inspire new posts

- A small one-time donation at Ko-fi - Thanks to everyone who’s supported me!!! <3

- If shirts and swag are more your style there’s some here - There’s a plane w/ dots shirt available!

- Buy one of my photo prints