Simplifying (reasoning about) complex systems

Amusingly a very NOT SIMPLE attack on the xz library to backdoor OpenSSH just broke over the weekend (decent summary from Arstechnica) in complete counterpoint to much of what I wrote about this week. Well, security and cryptography are definitely things where "simple" mental models don't quite cut it.

"How hard can it be?" – these are the famous last words of many a data science project. A lot of the work that we do involves guessing how a project will take and we are very much aware of how often we are wrong. So we all learn to be cautious about underestimating the difficulty of a project. It's an important skill to develop over a career. But I also think it's possible to take that caution a bit too far because there are times when we only need to know a simple, unnuanced explanation of how stuff works.

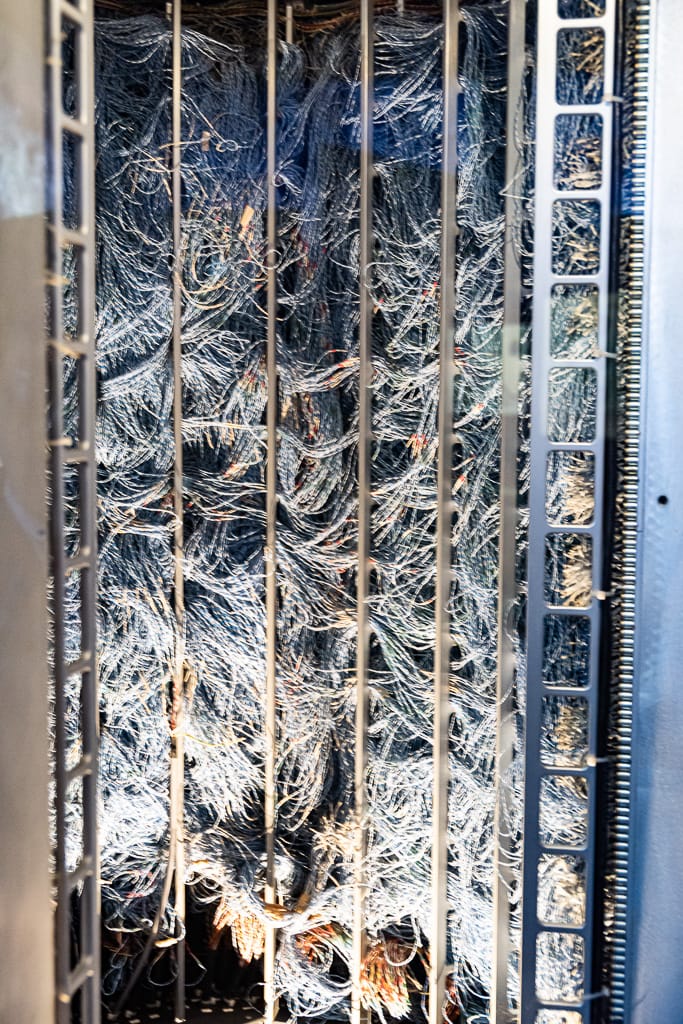

When zoomed out enough everything looks simple, while everything examined closely is extremely difficult. Since data folks come in contact with tons of fields and work at a mix of detail levels, we build an intuition about this. We very much see how sausage gets made not only in software engineering or data analysis, but also on the business side of things. We get to deal with the complexities when those systems are done "wrong" and make a mess of the data we're trying to work with.

But this intimate knowledge of complexity is also a problem – it makes us want to anticipate problems and fix them before it ever causes downstream trouble. This means that for many projects we consider, we wind up asking ourselves whether something is "really that simple". We do research, thought experiments, tests and all sorts of things to try to really answer how difficult it is to do something before we even set out to do something.

Despite this work we put in, even at the beginning, we already know in our gut that the answer is going to be both easy and hard at the same time. It's just very hard to be satisfied with that conclusion.

As an extreme example, take rocket engines. Rocket science is rightly considered to be Really Difficult stuff. Mistakes can cause untold amounts of destruction. But if you wanted to just build a toy rocket that shoots up into the sky for a few seconds – there's an instructible for making your own solid rocket engine. It is well within the abilities of a hobbyist. At the most fundamental level, rockets are just a tube of burning fuel where the hot exhaust gases are forced to go out in a single direction. If you do not care about details like steering or turning the engine on/off on demand, you can build one for minimal cost. All the super difficult stuff that gives rocket science it's reputation, all the metallurgy, chemistry, and design complexity only matter when you want more nuanced, controllable rockets. Those specific advances were created in response to problems encountered along the way to some goal. I doubt anyone developed advanced rocket patents out of pure amateur curiosity and imagination.

Going back to data science, think about the basic pattern needed for a data ingestion/ETL job. The pattern is literally on the tin – extract, transform, load. You obtain data, read it, do some transformations, then transmit the data somewhere else. This overall design pattern is consistent whether you're doing your first ETL job for a class project, or building out the most complex real-time analysis system on the planet. At a high level, it really is "that simple".

The complexity in design, and the source of our hesitation to write ETL infrastructure code, isn't coming from the immediate problem being solved, but many add-on considerations. How are we going to handle job scheduling? What about backfilling and handling failures? What about dependencies? What are the latency requirements? Are there any bottlenecks in the design? Everyone balances these concerns differently, and that's why you see so many different flavors of ETL systems out there, and why any ETL system has a surprisingly huge amount of code in it. It's easy to forget all this extra stuff is extraneous to the core concept.

My point today is that lots of other systems, not just in software, can also be understood under a framework of "really simple core idea, plus lots of complexity to handle edge cases". Honing your ability to understand systems at different levels of complexity is an important skill in our work.

Take point-of-sale systems that is ubiquitous in commerce. The core functionality is just recording what items are sold, at what price. In ancient times, people just kept track of these things in books at the end of the day, week, or whenever. Nowadays, this data can be gathered in real time and then aggregated and analyzed in countless ways. There's a ton of complex logic needed to handle edge cases like returns, discounts, coupons, promotions, etc.. Maybe you need to know those edge cases to do you work, and maybe you just need to know the core functionality that you can rely on the record of sales it generates.

Take web analytics systems. At the basic level, there's a system that increases a counter when something happens. There's lots of different mechanisms that can accomplish this task – a bit of JavaScript runs when someone visits a page and ticks a counter. Maybe a periodic job counts lines in the web server logs that fit a certain pattern and increments a counter that way. Way back in the 1990s, the first web analytics software just did those very simple things. You could slap something similar together in a quiet afternoon.

Just about every application in the world effectively boils down to an interface, a place to store information, and a bunch of business logic interlinking everything – the "Model-view-controller" pattern. There's hundreds of technologies that slot in to fulfill those functions, but the overall design is consistent. That also means that things we learn about the pattern in one context likely carries over into others.

We are surrounded by systems all around us that are both very complex and very simple at the same time. The gas coming into my stove has a ton of highly complex infrastructure to make it safe to use, but ultimately I turn a valve to release flammable gas and an electric spark makes fire. That simplified understanding is more than enough to get dinner cooked safely.

And so what I really want to emphasize today is how we shouldn't be afraid of the many systems that are around us. We shouldn't be afraid to implement systems just because a competing software system has so many more features already. By all means use the tools left to us by the people who came before, but know that it really is that simple to build a basic ETL or web analytics system as a starting point. Once you put those basics down, you'll start encountering all the edge cases that inspired other people to make their systems more complex, but you can handle them as you find need for them.

What's more important in this exercise of seeing systems at varying complexity levels is that you need to realize the same basic truths ALSO apply to problems where you can't find prior art to reuse. The modeling solution to a weird process only your company has can be approximately solved using "simple" algorithms too. Since you can't find any evidence to the contrary, maybe the simplest solution you can think of actually works. There's only one way to find out.

Data work loves to bask in the complexity of the tiny details of business logic – it's how we can make sure we count things correctly for analysis. But remember that there's value in both understanding the broader picture and also implementing a simple version of that broader picture.

Standing offer: If you created something and would like me to review or share it w/ the data community — just email me by replying to the newsletter emails.

Guest posts: If you’re interested in writing something a data-related post to either show off work, share an experience, or need help coming up with a topic, please contact me. You don’t need any special credentials or credibility to do so.

About this newsletter

I’m Randy Au, Quantitative UX researcher, former data analyst, and general-purpose data and tech nerd. Counting Stuff is a weekly newsletter about the less-than-sexy aspects of data science, UX research and tech. With some excursions into other fun topics.

All photos/drawings used are taken/created by Randy unless otherwise credited.

- randyau.com — Curated archive of evergreen posts. Under re-construction thanks to *waves at everything

Supporting the newsletter

All Tuesday posts to Counting Stuff are always free. The newsletter is self hosted, so support from subscribers is what makes everything possible. If you love the content, consider doing any of the following ways to support the newsletter:

- Consider a paid subscription – the self-hosted server/email infra is 100% funded via subscriptions

- Share posts you like with other people!

- Join the Approaching Significance Discord — where data folk hang out and can talk a bit about data, and a bit about everything else. Randy moderates the discord. We keep a chill vibe.

- Get merch! If shirts and stickers are more your style — There’s a survivorship bias shirt!